Revisiting a pre-pandemic classic, first published on Christmas Day, 2018. With an updated postscript.

Christmas day had a promising debut, with enough flurries to leave a thin frosting on a local business owner’s back deck. On Facebook he posted a photo of the scene, captioned, “A white Christmas in Fonthill.” It was an optimistic assessment, one that turned out to be true only briefly, as the sun, in hiding for so many of these past weeks, came out to melt what had fallen, and chase away what might have followed it.

By midday Highway 20 was doing a convincing impersonation of an empty runway running the width of Fonthill. No tractor-trailers barrelling down the hill, no teens in 10-year-old Toyotas, texting in their laps under the mistaken impression that no one can tell what they’re doing. East from Pelham Street to Rice Road, five sets of traffic signals habitually cycled between red and green, regulating zero flow.

The lights weren’t fast enough, though, for the lone driver on the scene. He had left Lin’s Chinese a few minutes earlier, and now waited to turn left out of the Food Basics plaza onto 20. In fairness, it had been a long wait while he was ignored by technology—longer that many would accept—before he pulled out and made his turn anyway, against God and the Highway Traffic Act. If the single constable theoretically assigned to all of Pelham had seen him, it surely would have been a Christmas miracle (and 3 demerit points).

Traffic was also in short supply on residential streets.

With nowhere to go aside from home and Netflix, people went walking instead. As usually happens on holidays, especially sunny ones, sidewalks became the busiest arteries. Every few blocks another couple or family could be seen walking their dogs or toddlers or both. No one hurried. Dogs indulged their noses without their leads being tugged. On Haist, just south of Canboro, a tiny sausage dog stuffed into a puffy red casing didn’t seem to mind the extra padding intended to keep him warm, even as he looked like a slow-motion cannonball on four tiny legs. He waddled along, ground clearance just adequate to keep Velcro from scraping concrete.

Across the street a man in a hurry proved the exception to the slow-Christmas rule.

He was now darting from his minivan to the entrance of pretty much the only game in town. While Giant Tiger and Sobeys and Food Basics are all abandoned ghost ships on Christmas day, the lights at the local Avondale stay on, a beacon to those in sudden need of that thing they swore they wouldn’t forget the eve before.

With the departure of their North Pelham location last March, two Avondales remain in town—one in Fenwick, the other at Haist and Canboro in Fonthill. The sausage dog bobbles on. Another visitor enters the store.

Greeting him the way she does everyone—with an apple-cheeked smile—store manager Darlene Sarvis returns to ringing up the man from the minivan, whose emergency purchase turns out to be disappointingly ordinary: milk.

Sarvis has worked at Avondale for 18 years, first as a cashier, then as a manager for three years in St. Catharines, then as manager in Fonthill since 2010. As management she’s on salary and doesn’t get paid overtime anytime, let alone on Christmas day. So why not assign the holiday to staff instead?

“Because I felt that I can’t ask them to work on Christmas day. They should be with their families.”

Sarvis said that at 18 and 21 her kids are older now, and Christmas morning isn’t the family event that it was a few years ago.

Yet in almost the same breath she acknowledges that this is her eighth Christmas appearance in a row.

Yet in almost the same breath she acknowledges that this is her eighth Christmas appearance in a row.

“I don’t mind that I’m working, because everyone who comes in is happy we’re open. They need something. And some people bring gifts. Someone brought in a Tim’s gift card and someone brought in a snack.”

She greets a customer who wants a pack of cigarettes then decides to buy two.

“I heard prices are going up,” he says. Sarvis nods.

While Christmas needs vary, each year there are a couple of constants.

“Everyone wants a newspaper,” Sarvis says. “And people are amazed that they don’t print on Christmas. They also want Tim Hortons coffee.”

Even during the rest of the year her store doesn’t sell fresh coffee, offering instead a Keurig machine.

“But the Keurig takes forever, people don’t want to wait.”

Last year the demand for coffee was so great that this Christmas Sarvis decided to play Caffeine Santa.

“I brought in my own percolator,” she says, waving at a white canister set up next to a machine dispensing something called “Slush Puppies,” a name suggesting, more than anything, “We’re carefully not infringing on anyone’s trademark here, okay?” A revolving rack of greeting cards, and a wire shelf of DVD movie titles as old as Sarvis’ kids, sit off to the side.

She shrugs.

“But so far no one has wanted any.”

This year’s hot item is eggnog. Apparently the local nog wells prematurely ran dry sometime on Christmas Eve.

Sarvis breaks the bad news to another seeker. “Sorry, we’re all out. Even Sobeys and Shoppers ran out yesterday.”

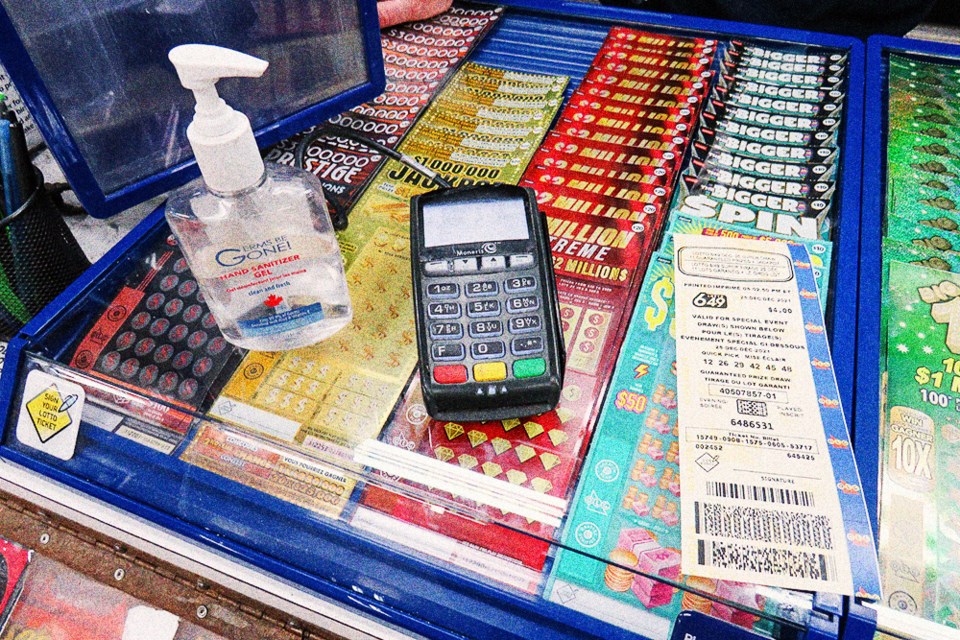

Another constant is the lottery. Sarvis does a brisk business, both in Lotto tickets and scratchers. It seems that every third customer wants to buy or cash-in a ticket. Lady Lotto’s recorded voice regularly competes with the radio station playing over the P.A.—“Winner! Gagneur!”

“We do a lot of lottery,” says Sarvis. “A lot.”

On the radio, Billy Joel’s “Only the Good Die Young” segues into Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin.’”

“It’s Top-40!” says a customer in his late-20s, dressed like a tidy lumberjack, eyeing the Cadbury bars stocked under a hinged cover in front of the cash register, “if this was 40 years ago.”

The young woman with him laughs ironically. They give off a suspiciously Toronto vibe.

Sarvis says the lottery business is the result of gift-giving. Tickets show up in stockings and cards, and inevitably there are winners, and winners want their winnings—even on Christmas day.

“Winner! Gagneur!”

(The OLG marketing people evidently took Sinatra’s “Luck be a Lady” literally.)

Another man in his late 20s, this one more customarily dressed, wins $50. He was already in the store a few minutes earlier, with a different winning ticket. He’s on a roll.

“Give me $40 in cash and $10 in tickets,” he says to Sarvis, then goes back out to his car. He sits behind the wheel and scratches, watched over by a young woman in the passenger seat.

Sarvis says that Christmas day business ebbs and flows, but on schedule each year it falls off a cliff right around 4 PM.

“By then everyone has what they need. That’s why we close at five.”

The scratcher man is back from his car, this time accompanied by the passenger, who turns out to be his wife. They have another winning ticket.

“We never win anything,” says Stephanie Henry. “We never buy them.”

Her husband, Blake, walks away from the register with their third round of tickets. They’re from Kitchener, in just for the day visiting family. Awhile back Stephanie’s parents moved to Fonthill from St. Catharines, where Stephanie grew up. Blake was raised in Welland.

“We got married in September,” says Stephanie, looking at the tickets in Blake’s hands. They agree to be photographed mid-scratch.

Sadly the streak comes to an end. No gagneur.

Sadly the streak comes to an end. No gagneur.

They say they’re driving home that evening. A quick calculation puts them $42 ahead in the scratcher department. Enough to bankroll the gas back to Kitchener, anyway.

An older man walks in and looks around uncertainly.

“Do you have coffee?” he asks.

Sarvis smiles and says, “Finally!” She comes out from behind the counter and heads for her percolator.

“Cream, no sugar,” says the man, whose name is Barrie McDowell. “How much do I owe you.”

Sarvis hands over a tall cup and tells him that it’s on the house. “There’s no charge at Christmas.”

McDowell is a retired cop, and lives a short walk away. He’s a regular, says Sarvis after he leaves. There are plenty of regulars. A woman drops a small mountain of sweet treats on the counter and Sarvis already knows that they’re for her daughter, who’s taken ill and lost her appetite.

“She needs to get something in her,” says the woman. Sarvis sends her off with get-well-wishes and a Merry Christmas.

A middle aged man stands in front of a refrigerated case, silently looking into it. He starts to make a call on his cellphone, then changes his mind. A moment later he’s gone, empty-handed. Maybe another a nog chaser.

Bruce Springsteen starts up over the P.A., but not with a Christmas tune. In fact, it’s possible that not a single Christmas song has played for the better part of an hour. Customers might be forgiven, after all, for wondering whether they’ve blundered into a time warp. As a destination, 1978 wouldn’t be half-bad, all things considered.

Golden-hued thoughts of decades past are interrupted by a call from across the aisles. It’s Blake Henry, heading back to his car for a fourth and final time. He holds up some cash.

“Hey, we won another $20,” he says, grinning.

The sun retreats and gray skies return. After Sarvis has closed up her store and gone home to her family, duty done, another brief round of flurries will fall later in the evening. Not a classic white Christmas by any stretch, but one well filled with the spirit of the day. ♦

Postscript | December 2022

Four Christmases later, nothing, and everything, has changed. Alpha, Delta, Omicron. Co-morbidities. How innocent 2018 was.

The idea of sauntering into a corner market without some sort of fabric barrier, elastic-strapped around our faces, is almost as impossible to imagine now as it is to believe there was ever a time that it wasn’t routine. Of course, a lot of folks dropped masks the minute they weren't mandatory any more. And so we've seen the deadliest year for Covid yet, surpassing 2020 and 2021.

At least the early flu surge now seems to have peaked. Covid cases are again on the rise, though. This postscript does not include an in-person update this year due to the fact that after three years of dodging the bullet, Covid finally caught up to your author, who tested positive last week. No doubt owing to being fully vaccinated and boosted, the symptoms so far have been mild.

The store, of course, today still stocks the obligatory pandemic necessities of hand sanitizers and face masks. Capacity limits are long a thing of the past, though.

A tall Plexiglas shield at the register, which went up early in the pandemic, finally came down this autumn, perhaps prematurely. Darlene Sarvis' husband, Fred, took a good shot a running for a seat on Niagara Regional Council during this year's municipal election. The incumbent won, and you have to imagine that the Sarvis household might be more peaceful without a politician in it.

A few minutes after five, Darlene will walk to the back and click a couple of light switches, leaving half the store dark. Then she'll pull a security gate—installed after a break-in last year—across the plate glass windows and prepare to lock up. She'll be there for another half hour or so, counting the cash, then head home, the world changed, the same, the future to come before the next Christmas Day unknowable, beyond the plain truth that it rests entirely in our own hands. ♦