If anyone on Regional Council was still unconvinced of the ongoing risks created by Niagara’s crumbling water and wastewater infrastructure—something detailed in a startling staff report last month—they didn’t have to wait long for further proof.

On September 9, a sewage pumping station in Fort Erie suffered a critical failure, setting off a cascade of events that resulted in raw sewage being discharged directly into the Niagara River.

The Lakeshore Road Sewage Pumping Station operates with two primary pumps that move sewage through the system for treatment. On September 9, the restraints for Pump Number 1, along with its electrical supply cables, deteriorated and snapped, causing them to fall into the wet well of sewage and immediately take the pump offline. The submerged electrical cables were then sucked into Pump Number 2, causing it to fail as well—while sewage continued to flow unchecked. As the sewage levels in the wet well rose, the overflow pump activated, but its only capability was to discharge the untreated sewage directly into the Niagara River.

The discharge lasted approximately 52 minutes and resulted in an estimated 5,300 liters of sewage being discharged directly into the environment.

According to a memo to members of council, “Staff visually inspected around the overflow and noted no signs of adverse effects from the spill.”

It’s unclear if any water testing was completed following the spill. Sewage contains a number of dangerous pathogens, viruses and bacteria, including E. coli.

“Typical municipal sewage is a foul cocktail of water, human waste, micro-organisms, disease-causing pathogens and hundreds of toxic chemicals. The principal pollutants found in sewage include pathogenic bacteria and viruses, oxygen depleting substances (measured by Biological Oxygen Demand or BOD), various suspended solids and nutrient pollutants like phosphates– each of which carry a heavy ecological toll when released into a fragile ecosystem,” a report from Ecojustice details.

The harmful leak came just four days after Regional councillors heard from staff about the deteriorating state of the Region’s water and wastewater infrastructure.

As previously reported in The Pointer, on September 5 Terry Ricketts, Commissioner of Public Works for Niagara Region, presented a report to council outlining the serious consequences of years of underfunding for water and wastewater infrastructure. She described how this lack of investment has created what she referred to as a “gap between the perception of the status of water and wastewater services, and the reality.”

Framing her report as fulfilling a “legal duty to share specific information,” Commissioner Ricketts’ presentation was a call to action. She reminded council of its obligation under governing legislation to "meet the required standards for water and wastewater quality, and ensure systems are maintained in a fit state of repair.” She emphasized her responsibility to provide council with the necessary information for decision-making and underscored her overarching duty to public welfare. It was a compelling call for council to grasp the gravity of the situation.

In response to questions from The Pointer, Phill Lambert, Director of Water-Wastewater Services at Niagara Region, confirmed that the Lakeshore Sewage Pumping Station was classified as being in "very poor" condition, as defined in the September 5 report. The facility is scheduled for major capital upgrades beginning in early 2025, with regular maintenance continuing until the structure is eventually replaced.

Lambert explained that, "all of our plants, pumping stations, and other infrastructure are equipped with electronic metering and level sensors that allow us to continuously monitor equipment operations in real time and quickly alert staff to potential issues."

This system triggered alarms, notifying staff of the problem. Crews then responded to the site to inspect and address the malfunction, conducting visual inspections of the overflow area to ensure no debris required removal.

The facility had been flagged for upgrades as early as 2015 and again in 2021—but these upgrades were deferred. While Lambert urged caution against drawing broad conclusions from the Lakeshore incident alone, in the context of Commissioner Ricketts’ September 5 presentation to council, it is evident that further delays in investing in Niagara’s critical infrastructure are no longer advisable.

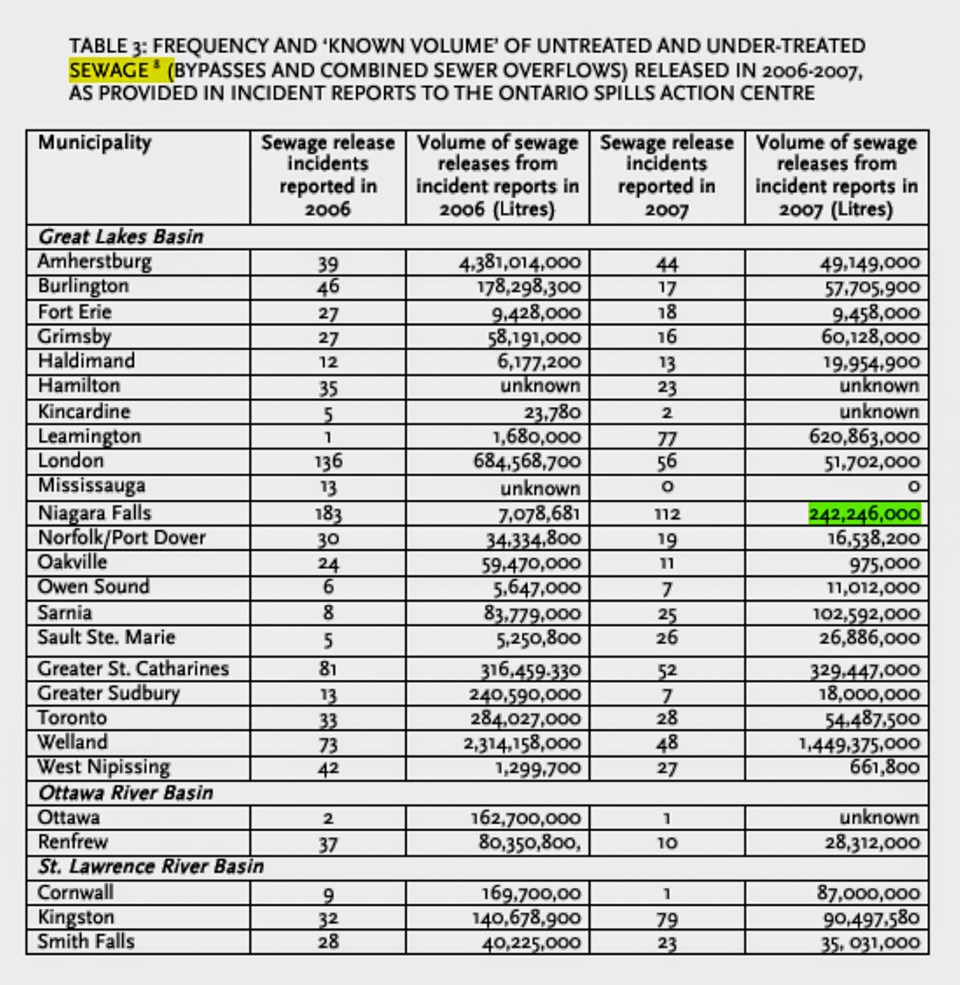

In May, the Region received warnings from the federal Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change for numerous infractions related to wastewater management, including a spillage reported as an "acute toxicity exceedance." This further underscores the urgency of addressing Niagara’s deteriorating water and wastewater infrastructure.

The severity of the situation can not be a surprise to council. As Mayor Wayne Redekop (Fort Erie) pointed out on September 5, “this isn’t something new—we’ve been hearing about the infrastructure funding gap for years.”

Council’s priorities are made clear through its budgeting decisions. By allocating substantial funding to certain initiatives while underfunding others, they are sending a clear message about where their values lie. Recently, council extended incentive programs for developers that costs taxpayers tens of millions of dollars with little measurable gain, all while critical infrastructure continues to deteriorate. As staff have repeatedly warned, these issues cannot be ignored any longer.

The September presentation illustrated that regional investment in water is at about half (49.2 percent) of what it needs to be, while wastewater is even more underfunded at a rate of approximately 20 percent of the current need.

Regional staff have already highlighted that: 77 percent of the Niagara Region’s water is delivered by three plants that are approximately 100 years old (collectively, these plants have a backlog of more than $280 million in overdue investment for repairs and equipment that is in very poor condition); 44 percent of the Region’s water facility assets are deemed to be in poor to very poor condition; 90 percent of the wastewater capacity is delivered by plants more than 50 years old—collectively, these plants have an investment backlog of more than $400 million.

Ed Smith is a Local Journalism Initiative Reporter based at The Pointer.