This story was originally published in August 2017.

Travellers searching for traditional accommodations in Pelham have few options. Hipwell’s Motel can be found in the phone book, where it has been reliably listed for the past eighty years or so. The Fonthill Inn, a more recent addition, is in the Yellow Pages too, and provides a little more luxury in its downtown rooms. And that’s it. The nearest true hotels are in either Welland or St. Catharines.

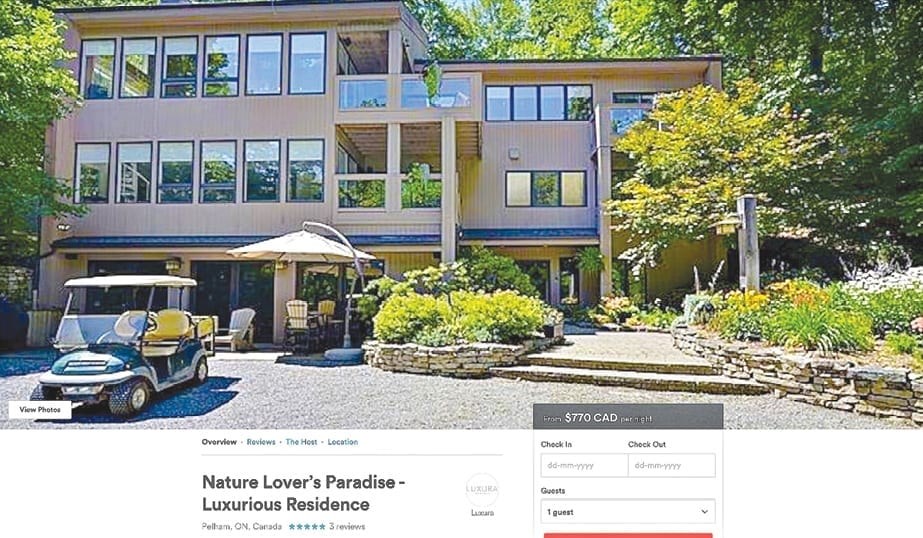

Pelham is still a small town, after all, and neither Food Basics nor Dollarama are likely to lure overnight visitors. But on Airbnb, an online service that brokers arrangements between travellers and homeowners, there are nearly 20 other options for people who want to spend time in Pelham for reasons not involving discount shopping. Listings run from a one-bedroom apartment for $51 a night, to a palatial 10,000 sq. ft. compound with a private gym, steam room, and basketball court—for $770 a night plus a $200 cleaning fee.

Founded in 2008 by some Americans in their 20s trying to make the rent, Airbnb has ballooned in popularity over the past decade. Airbnb’s service is simple, and it has variety of safety measures, including an extensive rating system that allows guests and hosts alike to post public evaluations of the people they’ve encountered.

In a recent US radio interview, co-founder Joe Gebbia recounted that early-on the site had to combat something “we’ve all been taught since we were kids—strangers equal danger.”

Since Airbnb was intended initially for people to rent out rooms in their own homes (or, as Gebbia first did, an air mattress on his floor), investors were unwillingly to believe that people would want to invite complete strangers to sleep in the next room. Those early naysayers were proved wrong, and are no doubt rueing their lack of foresight. While it is still privately owned, analysts have valued Airbnb at $30 billion dollars.

There are now some three million listings on the site, in 191 countries. An estimated two hundred million people have used the service over the past eight years.

Fonthill resident Phillip Raney has been hosting people on Airbnb for nearly two years. He’s unsurprised by the site’s popularity. Raney previously worked at a hotel in Niagara Falls, but tired of the 70-hour weeks. Once they moved in to their home in Fonthill, Raney’s husband suggested that he take some time off work. After a few months, Raney grew bored and decided to try Airbnb.

“I can’t even describe how amazing it is,” he said. “The connections that you make with people are just unbelievable.”

Though Raney has returned to work in the food industry, his home is now booked nearly solid through most of the summer, and much of his free time is spent organizing the stays of his guests. Four rooms in his five-bedroom home start at $100 per night, but Raney says that the entrepreneurial element comes behind the pleasure of meeting travellers and sharing his passions with them. Each morning, he cooks his guests a gourmet breakfast with homegrown ingredients and educates them about the process as he does it. All of this has evidently gone over well with his guests: he has a perfect five-star rating and says that, “Easily ninety percent of the people who have stayed with us follow me on social media, and we keep in touch later, after they’ve left.”

Raney’s enthusiasm for Airbnb is shared by another Pelham resident, Eli Willms. Along with his wife, Hannah, Eli has lived for the past year in a house in Effingham that also hosts Airbnb guests. The couple live in a basement apartment in the home, and Eli says that he occasionally doesn’t even notice the Airbnb guests coming and going.When he does, his interactions have been overwhelmingly positive. He says that his landlords, who also live in the house, are eager to share their property with as many people as they can, and he understands why.

“This is such a beautiful place,” Willms says. “It’s so exciting to meet people travelling and to hear their stories.”

The connections that you make with people are just unbelievable

This proximity to Airbnb has led him and his wife to hope that one day they’ll be able to host travellers too. They even joked about putting the pull-out couch in their basement apartment on the site—a “nesting-doll listing” of sorts.

Elsewhere, Airbnb’s emergence has encountered opposition. The New York Times recently reported that the American Hotel and Lodging Association had developed a “multipronged, national campaign approach at the local, state and federal level” to combat Airbnb’s advances. The Association argued that Airbnb had forced hotels to lower prices, especially during holidays, conventions, and other big events when hotels make most of their revenue. The Association’s Vice President Troy Flanagan said that, “Airbnb is operating a lodging industry, but it is not playing by the same rules,” referring to the taxes hotels must pay and the safety and security obligations they have.

A study from McGill University released last week suggests that Flanagan may be right. While Airbnb depicts its users as regular homeowners renting out rooms to help pay the mortgage, the study argues that just ten percent of homes account for the vast majority of nights booked in Canada’s three biggest cities. Principal author David Wachmuth told the CBC that property management companies are taking advantage of the site and are essentially operating hotels. "There's one in Montreal that has about 160 properties," said Wachsmuth, who estimated that it makes, “a couple of million dollars a year on Airbnb.” Airbnb disputes the study’s findings, and maintains that 80 percent of its listings are from people sharing their primary residence.

In Pelham, it appears as though only two Airbnb properties are operated by professionals—most notably The Fonthill Inn, which lists its rooms on Airbnb and receives about ten percent of its reservations from the site. Owner Elizabeth McGill says she is pleased with that ten percent, though her use of Airbnb differs in that she has little face-to-face interaction with guests.

And then there’s that 10,000 square foot mansion, managed by a vacation rental company called Luxura. The firm, which initially agreed to speak to the Voice on the condition that no employee be identified, later went silent. According to Airbnb, Luxura has six other listings in Niagara and has rented these listings some 80 times.

Airbnb’s ascendence has not come without cost, even in Pelham. The owners of Hipwell’s have seen a substantial drop-off in certain sorts of guests over the past few years.

“We don’t see many families any more,” they said. “Before the past few years, there were lots of them, staying here with kids.” Business has been steady at the motel, largely because of construction teams working on the wind turbines, but Hipwell’s is still unhappy that it and the rest of the industry must meet certain legal standards, while Airbnb hosts need only meet the site’s guidelines. “They should have tax on them, as well,” they added. “We end up paying more property tax [than on a private home], plus the tax on the rooms—we can’t afford to drop the prices down.”

Many of the complaints from the hospitality industry have centred on taxation, and as with all matters involving the taxman, this one is complicated. Property owners who earn money from Airbnb are supposed to declare these earnings as rental income, but others, who provide more services for their guests such as laundry or meals, are supposed to be taxed as businesses. These rules become even murkier if a non-primary residence is being rented.

The end-result of this confusion is that Airbnb hosts often pay fewer taxes than they should, many pay none, and nearly all pay lower percentages than hotels, since hosts do not pay commercial property taxes. In cities, where the McGill study argued that many Airbnb hosts are running de facto hotels, this issue is particularly acute.

Financial matters are not the only questions to be raised about the site’s broader effects. Airbnb requires real names and strongly encourages guests to include photos of themselves on their profiles. Many have argued that this allows for racial discrimination in the service. A 2016 study by the Harvard Business School suggested that booking requests from accounts with “distinctively African-American names” were 16 percent less likely to be accepted. While Airbnb has sought to combat this perceived problem, the very nature of the service—with its focus on the personal connections that Raney and Willms so love—means that explicitly illegal actions such as racial discrimination are difficult to prove.

Last week, Airbnb was again subjected to criticism when it permanently banned certain users from its site. The “Unite the Right” event in Charlottsville, Virginia, which took a violent and tragic turn last Saturday, saw white nationalists from around the United States looking to book accommodations in the area. After being advised of the rally’s nature, Airbnb identified the accounts of those affiliated with the far-right gathering and shut them down. It asserted that it was doing so to bolster its policy that Airbnb members, “accept people regardless of their race, religion, national origin, ethnicity, disability, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, or age,” but the action nevertheless raised questions as to whether the company was screening the political beliefs of its users. That said, when political action morphs into terrorism it’s unlikely that any but the most doggedly academic observer would seriously argue that people should be required to accept Isis fighters, or Neo-Nazis, as guests in their homes.

It’s clear that the very personal nature of hosting people in homes will almost inevitably lead to hosts exercising a great deal of “choosiness,” in one form or another—including in Pelham. After one mildly unpleasant experience, Phillip Raney began vetting his prospective guests more rigorously.

“I’m rather particular in how I pick out who the guests are,” he says, emphasizing that with Airbnb there must be a deep mutual respect, since guests and hosts share the same space. Raney responds to occasional impersonal requests from people “just coming to visit the Falls” with a polite explanation of how Airbnb differs from the traditional hospitality industry.

Above all—and this is the part that he and Airbnb truly appear to believe—Airbnb is a different sort of service for a different sort of traveller. Many of Raney’s guests come to Pelham for nearby wine tours and weddings, and some nuptial parties have turned their time at his home into part of the festivities, hosting their hair and make-up gatherings with his permission. He makes them a gourmet breakfast, and invites them to have tea in his traditional Chinese tea room.

“There are some people just looking for a cheap place to stay,” Raney says. “But nearly everyone I host wants to have an experience. And that’s what I try to give them.”