Longtime family practitioner agrees never to seek licensing again—anywhere in Canada

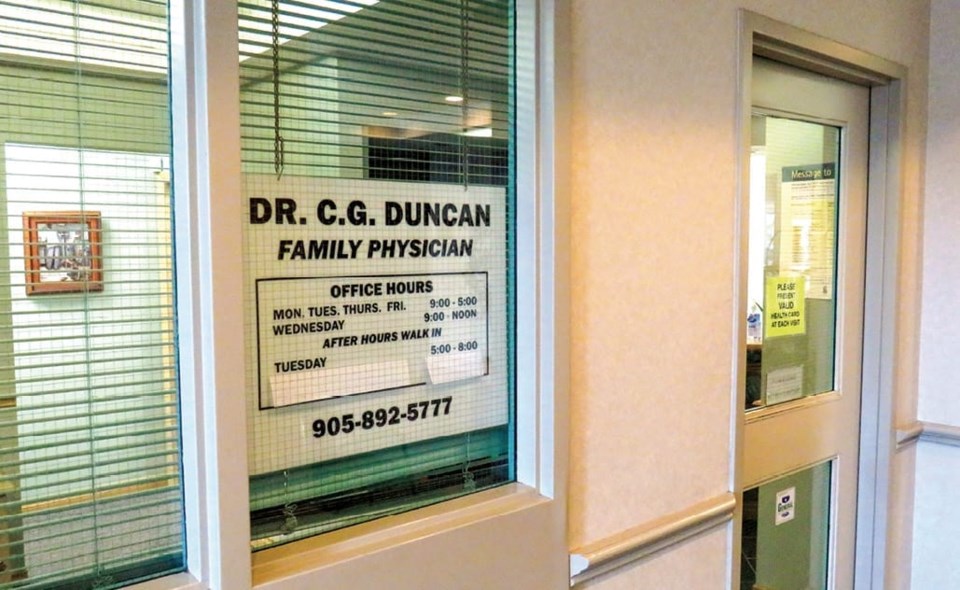

Dr. Charles Duncan, whose family medicine practice has been a fixture for decades at the corner of Highway 20 and Rice Road in Fonthill, has resigned from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO). He has further agreed not to seek a medical license again in Ontario, or elsewhere in Canada. Duncan’s resignation is effective October 31.

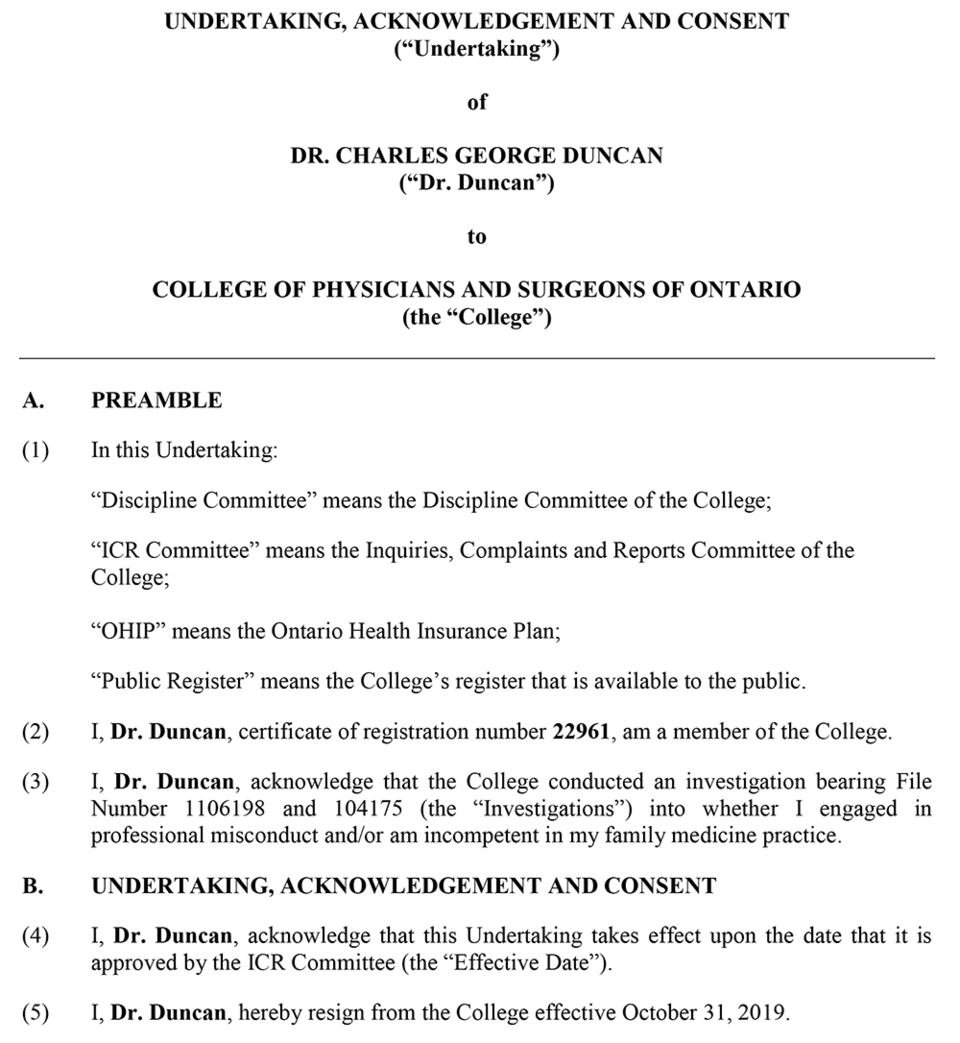

Following a months-long investigation by the CPSO, the institution publicly released the terms of Duncan’s resignation on Thursday, August 22. Summarizing the document—known as an “undertaking”—the CPSO stated: “College investigations were conducted into whether Dr. Duncan engaged in professional misconduct or is incompetent in his family medicine practice. In the face of these investigations, Dr. Duncan resigned from the College and has agreed never to apply or reapply for registration as a physician in Ontario or any other jurisdiction.”

The undertaking is publicly accessible on the College’s website. Shortly after it was posted, an individual related to a woman who alleges being twice sexually assaulted by Duncan contacted the Voice to bring the document to the newspaper’s attention.

The woman herself ultimately agreed to speak on the record about her experiences with Duncan, though on condition that the newspaper withhold her name. She met with the Voice last Saturday, a short distance from her parents’ home in Fonthill. She answered all questions asked of her, and provided copies of a police report and emails which she asserted bolstered her allegations.

For simplicity, the woman will be referred to as “Jane Smith,” and hers was not the only claim made against Duncan. In fact, Smith’s involvement in the CPSO’s investigation nearly didn’t happen at all. A CPSO investigator looking into another claim against Duncan contacted Smith at the last possible moment, late last winter.

Smith answered the phone at work one day in March.

“I got this cold call from an investigator at the CPSO….My response was, ‘Is this a joke?’ It was complete disbelief.”

The investigator assured Smith that she was serious.

“She said, ‘I have been looking for you for months.’ So it was just— my mind was blown at this. This woman had been looking for me to cover all of her ends as an investigator and she found me. It felt fated.”

The investigator told Smith that this was scheduled to be her final day on the case.

“It was her last attempt to locate me before she closed the file on the complaint.”

The delay in tracking Smith down was due to a change of name. She had married and taken her husband’s family name. But ten years earlier, in her first job in the medical profession, she had been hired by Dr. Charles Duncan, under her maiden name, at his practice in Fonthill.

It was in Duncan’s office and exam rooms that she alleges the sexual advances and assaults occurred. At the time, Duncan was in his 60s. Smith was in her 20s.

The Voice tried repeatedly, through email, telephone calls, social media, and an in-person visit to his office, to obtain comment from Duncan related to his resignation, and to the allegations made by Smith. He had provided no response by press time.

From the investigator, Smith learned that the CPSO was looking into other allegations made against Duncan.

In the course of their investigation, the CPSO sought to contact all current and former staff involved with Duncan’s practice. The investigator was unaware that Smith herself had allegedly been assaulted by Duncan a decade earlier.

In fact, almost no one knew.

Following the incidents, which Smith said occurred a week apart—both happening while she was alone with Duncan—Smith told only her immediately family, and later her husband, what had transpired.

She also, a few days later, on July 6, 2009, told the Niagara Regional Police.

Smith provided the Voice with a copy of an NRPS incident report from that date, describing in detail Duncan’s alleged actions. Smith said that she filed the report for informational purposes only, and specifically told the police that she did not want to bring a criminal complaint against Duncan.

“I struggled with it for maybe a week and I chose to make a police report, an information police report...the intention behind it was to help another person, to document it, to give credence in case somebody else comes forward, and I left it, and that was it.”

And indeed that was it—for a decade.

In both the incident report and in her recollection of events when speaking with the Voice, Smith described herself as young, trusting, and initially “naive” about the nature of Duncan’s behavior towards her.

“It didn't start out right with the assault. I was groomed for that assault. It was hand on my shoulder, friendly, stuff like that. I mean, I looked at him paternally as a trustworthy older man who would not see me in that light, you know?”

Smith started working for Duncan in October 2008, as a lab assistant, taking blood, performing ECGs and pulmonary function tests, and administering injections. It was a part-time job in the mornings. In the afternoons she would go on to a second job at a Niagara Region hospital.

In part, the 2009 police report reads, “[Smith] advised that Dr. Duncan is very affectionate with his staff and several times a week he asks her into his office and shuts the door. [Smith] stated Dr. Duncan would stand very close to her and rub her shoulders, or he would sit in his chair and rub his hand up her inner thigh. [Smith] advised that she would move away when Dr. Duncan would make sexual advances but admits that she was very naive and didn't want to believe what he was doing was on purpose. [Smith] advised that she didn't tell him to stop, but she did move away and leave the room. [Smith] advised that she was afraid she would lose her job if she said anything. [Smith] advised Dr. Duncan's sexual touching was progressively getting worse over time to the point that she would go out of her way to stay away from him.”

On June 23, 2009, Smith had two moles removed at another medical facility. The next day, she asked Duncan whether he would examine the stitches and eventually remove them, saving her having to book an appointment with her family doctor.

“Because I couldn't see—there were two stitches, one in my armpit and one in my back. And I asked him, ‘Can you just have a look at them and make sure they're good, they're not infected?’ I trusted him. He was older than my father.”

Smith says that she went into an exam room and lay on her side on the examination table, facing away from Duncan.

From the 2009 incident report: “[Smith] advised she didn't remove her shirt, she just lifted it high enough to show the stitches. [Smith] stated that Dr. Duncan stuck his hand down the front of her shirt and stated, "Oh nice." [Smith] stated he took his hand out so fast she was still in shock with what he had just done to her. [Smith] stated he pretended it didn't happen, and after looking at her stitches he left the room.”

Smith said she left work in a daze.

“I told my parents right the same day. I left his office, I finished at one o'clock over there, and I went straight there.”

She said both parents were upset. Her father was ready to confront Duncan immediately.

“But my mom, she was very much aware and concerned that if I took it to the CPSO, that my character could possibly be destroyed as the result of it.”

Smith said she feared being labelled a troublemaker.

“This was my first steady [medical] job and what I thought was a reputable office. I enjoyed the patients. I enjoyed what I did. And at what cost?”

Smith also wondered whether she had inadvertently sent sexual signals to Duncan, who was married with a family.

"Am I guilty? Did I smile too much? Did I laugh too much? Did I do something to give him the green light that this was okay?"

Even at the time, however, Smith said she knew that what Duncan had done was wrong, and the passage of time has strengthened this conviction.

“I know now...that this was never about me. Now I see that. Ten years ago, I didn't have the wisdom, the understanding, the life experience to see that. I think you grow up and things that had a blurred line in your 20s are a nice straight, hard line in your 30s, right? I think that's a universal growth.”

Two days later, Duncan, who had never emailed Smith before, did so, asking how she was feeling. Smith replied that she was fine, and would be back in the office the next day. Duncan replied, “Do I have to wait that long? Just kidding…. I will get back to work and leave you alone. Take care.”

Smith provided copies of these and other emails to the Voice, emails she said that she also gave to the CPSO.

A week after he allegedly groped Smith, Duncan asked her whether she was ready to have the stitches removed.

“He says, ‘I can come and I can take your stitch out.’ And I'm frozen. I'm frozen. Do I say, ‘No, I don't want you to,’ in front of the receptionist, you know what I mean, and make waves, and resist? So, I walked in.”

From the 2009 incident report: “[Smith] stated she removed her shirt and held it in front of her breasts. [Smith] stated Dr. Duncan unclasped her bra, and she [held] her shirt up to her breasts and sat on the examination table. [Smith] stated when Dr. Duncan was cleaning the stitches in her [armpit] he tried to pull down her shirt and uncover her breasts. [Smith] stated she resisted and Dr. Duncan stated, "Come on, I've seen tons." [Smith] stated she replied "That doesn't matter." [Smith] stated he removed all the stitches and when he was finished he leaned in to kiss her on the mouth. [Smith] stated she turned her head and said, "Come on Dr. Duncan." [Smith] stated she left the office and went back to work.”

Smith said that she was “100 percent” certain that Duncan was seeking a sexual affair.

Again rattled, but also increasingly angry, Smith went home and emailed Duncan to express her feelings.

On June 30, 2009, she wrote, “Dr. Duncan, I just want you to know that I was totally not okay with what happened today when you were taking out my stitches. I realize that you are a very affectionate employer but you crossed the line today and I don't want it to happen again. I also don't want to talk about this at work. In fact, I don't want to talk about this again. Please respect my feelings and my right to work in an environment where I am not apprehensive to be behind closed doors with you. See you Thursday.”

Sixteen minutes later, a 3:28 PM, Duncan replied: “I apologise if I offended you and it won’t happen again. Probably best if you don’t ask me to provide medical care for you and then we can keep our relationship totally professional. We have been kidding with each other and that has made it difficult to draw a line but will do so. Enjoy your day off.”

After again discussing her situation with her parents, Smith decided to file the police report, but not to press charges.

“We have all been conditioned to not say anything, not do anything. What if it came back and I was labeled a…. What if he says I was [trying to seduce him].”

Smith returned to work, where she said relations with Duncan were “icy” from then on. Three months later she took a full-time job in the Niagara Health System, and has not seen Duncan since.

Smith’s decision to document the incidents as a means to help other potential victims remained dormant for a decade—until the CPSO called in March. It was a call that sent her into a tailspin.

Smith said that over the ten years she’s worked in the NHS, she has received consistently positive performance reviews. She has not been subject to any unwelcome sexual advances, or other untoward behavior from colleagues or supervisors. She married, and has two children.

The call “unlocked a box,” and brought feelings she had repressed for a decade back to the surface.

The CPSO investigator asked if Smith would be willing to file a formal complaint with the College.

“I had to look back at my intention ten years ago and that was to help another person. So there was no hesitation for me, even though I would be exposed, my name would be out there, Dr. Duncan would know that I was the second complainant, they know.”

Smith said that the CPSO would not disclose to her, even in general terms, who the other complainant was.

“We're living in a society right now where there are, I'm sure, lots of women that this has happened to. You don't come forward, you don't come forward, and the bravery that it took for this person to come forward. I don't know if it was a woman, I don't know if it was a male...an employee, a patient. I don't know if it was a young woman, a senior woman.”

Despite agreeing to help the CPSO, Smith said that the anxiety over doing so, and the process involved, left her emotionally drained.

Investigators came to interview her at home. They requested that she show them the scars where her moles had been removed.

“[They were] there for three hours, and I had to draw my memory of the exam rooms. Where was I positioned? Where was he positioned? They took pictures of the scars of the moles that were removed, the stitches that were removed.”

Smith said that through April and May she was “a mess.”

“Just being seen by him again, you know what I mean? Not visibly seen, but I was going to come back up in his life and he was going to know it was me, which is pretty scary.”

Smith began seeing a therapist.

The CPSO kept her informed throughout, she said. Duncan steadfastly maintained that he had done nothing wrong—either with Smith, or with the other complainant. By August, the cases were set to go before a CPSO investigative committee—the equivalent of a grand jury—which would decide whether there were sufficient grounds to proceed to a full disciplinary hearing, the equivalent of a trial.

“Absolutely there was enough to move it forward to a disciplinary hearing,” said Smith. “And at that point he is found guilty of professional misconduct or he is found not guilty of professional misconduct. It's basically a trial where I would witness, I would go on the stand and I would be cross-examined by his team of lawyers or lawyer or whatever. And I would have to be prepped and everything like that by the lawyers at the CPSO. And I was willing to do that.”

To her regret and relief, in the end Smith wouldn’t be required to do so.

On the day that the committee began its deliberations, Smith said that an attorney representing Duncan preemptively presented the “undertaking” agreement, in which Duncan—without admitting guilt or liability—voluntarily agreed to resign, and not to reapply for a medical license in any jurisdiction.

CPSO Senior Communications Advisor Shae Greenfield told the Voice that had Duncan effectively gone to trial and been found guilty, the loss of his Ontario medical license would not have prohibited him from seeking to practice elsewhere in Canada. The undertaking, however, does stop him from doing so.

“This is a more significant outcome than we would've been able to achieve by pursuing a contested disciplinary hearing,” said Greenfield. “I think that's worth keeping in mind.”

Greenfield said that he was prohibited by law from revealing even the general nature of any other complaints against Duncan, or any personal details about who may have filed them.

Asked whether the two-month delay between Duncan’s agreement to resign and his actual departure was unusual, and possibly represented an ongoing risk to Duncan’s patients, Greenfield paused and seemed to want to choose his words carefully.

“What I would be able to say, is that, in general terms, the College would not allow a physician to remain in practice where there was concern, an immediate concern about the safety of the public. And, obviously, you can infer from that. But that would be the issue that I, again, under the Regulated Health Professions Act, I wouldn't be able to speak to the specific considerations involved.”

Smith said that she was informed of the committee’s decision the same day.

“I got the call just a couple hours after by the investigator to let me know the result of it.”

The Voice has learned that Duncan has approached at least three Niagara physicians in recent weeks, asking whether they could take his patients, estimated to be “in the hundreds.” To the newspaper's knowledge, none agreed.

Smith wasn’t surprised by the outcome, saying that CPSO investigators told her that Duncan would most likely quietly retire in the face of the evidence gathered.

She shook her head.

“But an innocent man doesn't do that, with a 40-year practice in a small town.”

Smith said she wants the other complainant in the investigations to know that she supports them—and others who may not yet have the ability to come forward.

“My mom says to me, ‘You let that reporter know that the Jeffrey Epsteins of the world are alive and well in sleepy Fonthill.’ [But] these assaults don't just happen to young teenage girls. We have to be aware that there are people in positions of power. It could be a woman, it could be a male. But in my experience, I was assaulted by a male in a position of power. He was a doctor, he was my boss.”

Smith pointed to a paragraph in Duncan’s undertaking, where her case and that of the other complainant are identified by numbers.

“To number 1106198, there was no way I wasn't going to be there. I have to look back at what my intention was ten years ago and remain true to that, which was to help another person. I would love for the other complainant to know I was always going to have her back.” ◆

RELATED: Pelser's abrupt departure explained RELATED: Ten more women emerge with Duncan assault allegations